No U.S. Landfalling Hurricanes in 2025 Refutes Alarmist Rhetoric on Weather Extremes

/It’s like a football game where one team didn’t show up.

Or champagne without the fizz.

Or Christmas without the tree.

That was the U.S. 2025 hurricane season, in which not a single Atlantic hurricane made landfall in the U.S. And this despite the steady drumbeat of articles in the mainstream media and pronouncements by climate alarmists, proclaiming that weather extremes such as hurricanes are on the rise.

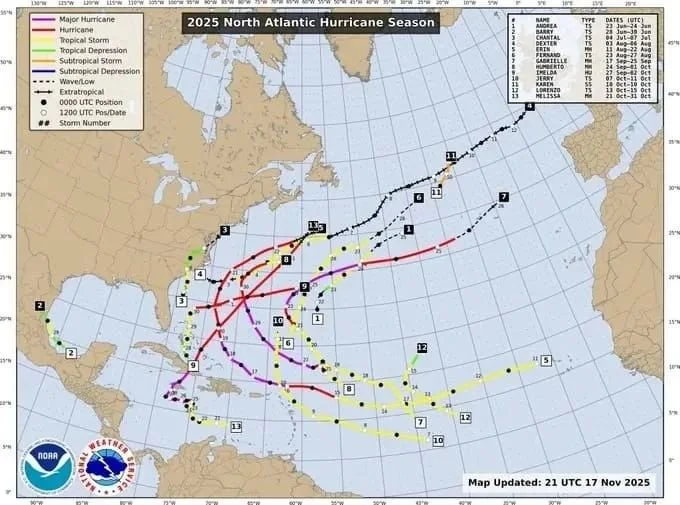

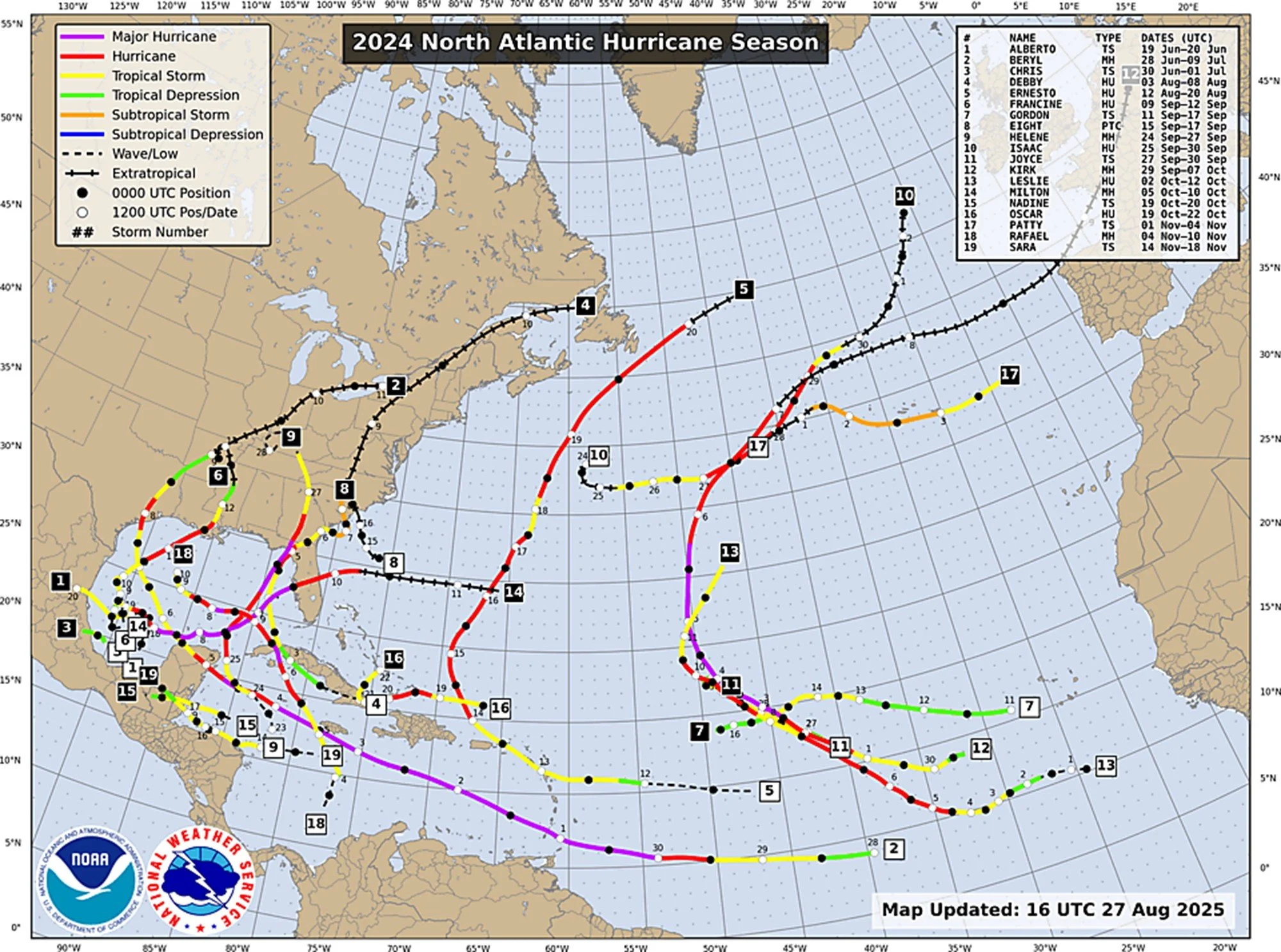

The 2025 no-show is illustrated in the figure immediately below; the second figure shows the much more active 2024 season.

The closest to landfall of the 2025 hurricanes were tropical storms Barry (2) and Chantal (3), neither of which actually qualifies as a fully fledged hurricane. Tropical storms have sustained wind speeds up to 117 km per hour (73 mph), while the weakest Category 1 hurricanes have top wind speeds from 119 to 153 km per hour (74 to 95 mph).

Although the last time no hurricanes made landfall in the continental U.S. was in 2015, the preceding 15 years from 2000 to 2014 saw the same phenomenon no less than 6 times. Before that, the decades of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s each saw just 2 landfalling hurricanes. Clearly there is no pattern or connection to climate change, as the globe was cooling in the 1960s and early 1970s, but has warmed since then.

The total number of all North Atlantic hurricanes or major hurricanes in 2025 and 2024 was 9 and 16, respectively. The lower number in 2025 is reflected in what is known as the Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the North Atlantic Basin. The ACE index is an integrated metric combining the number of storms each year, how long they survive and how intense they become.

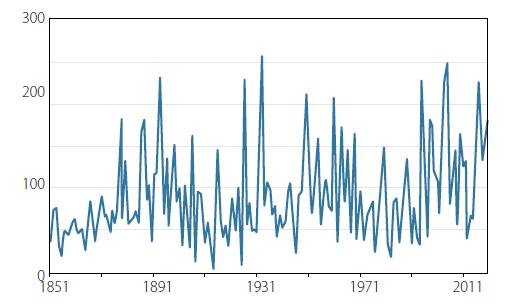

The next figure shows the ACE North Atlantic index since 1851. The highest index in the record was 259 in 1933. The 2025 no-landfall season had an ACE index of 133 (measured to December 4), which is just slightly higher than the long-term average; the index for 2024 was 162.

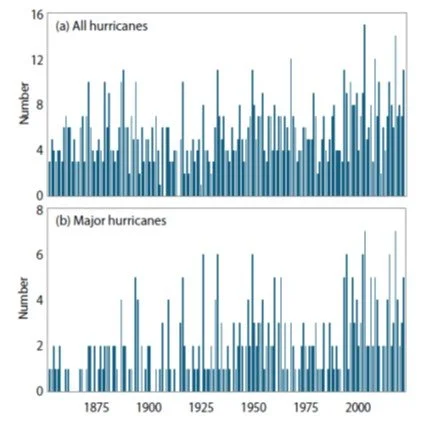

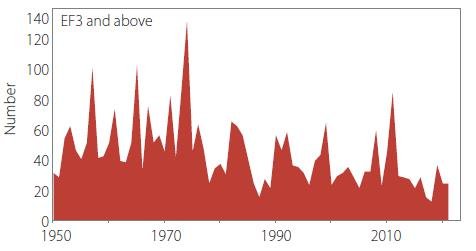

A comprehensive report on 2024 hurricanes by UK climate writer Paul Homewood, discussing long-term trends in North Atlantic hurricanes, found at that time no evidence for any increase in hurricane frequency, intensity or both associated with global warming. Homewood’s compilation of frequency data for North Atlantic hurricanes and major hurricanes from 1851 to 2024 is presented in the figure below.

While it may appear from the figure that hurricanes have indeed become more common since the 19th century, Homewood points out that the apparent increase “has been due to changes in observation practices over the years, rather than an actual increase” – as concluded in a 2021 study by a team of hurricane experts. Prior to the satellite era, which dates only from the 1960s, many storms were not spotted at all.

Back then, most data on hurricane frequency in the U.S. was based on eyewitness accounts, thus excluding most hurricanes that never made landfall – as well as many landfalling ones in sparsely populated areas. And even the recording of non-landfalling hurricanes relied on observations made by ships at sea, which almost certainly resulted in an undercount. So it is hardly surprising that the public falsely sees today’s more complete coverage enabled by satellite technology as an uptick in hurricane occurrence.

The perception that extreme weather events are increasing in frequency and severity is primarily a consequence of modern technology – the Internet and smart phones – which have revolutionized communication and made us much more aware of such disasters than we were 50 or 100 years ago. Before 21st-century electronics arrived, many hurricanes and other weather extremes went unrecorded. The misperception has only been amplified by the mainstream media, eager to promote the latest climate scare.

Another aspect of hurricane measurement is maximum wind speeds. There is growing evidence, says Homewood, that wind speeds of the most powerful current hurricanes may be overestimated compared to those in the pre-satellite era, because of changing methods of measurement.

In the past, hurricane wind speeds were estimated from the central pressure of the system, which could be more readily measured. But more recently, wind speeds have been calculated from satellite and aircraft data. This has created an anomaly, because estimates of wind speeds for hurricanes now tend to be higher than past ones with similar central pressure. What this means is that wind speeds before the advent of satellite technology were underestimated in comparison with hurricanes today.

As with frequency, the data clearly reveals no evidence that hurricanes are becoming more intense, or that extremely intense ones are becoming more common, as global warming continues.