Extreme Weather in the Distant Past Was Just as Frequent and Intense as Today’s

/In a recent series of blog posts, I showed how actual scientific data and reports in newspaper archives over the past century demonstrate clearly that the frequency and severity of extreme weather events have not increased during the last 100 years. But there’s also plenty of evidence of weather extremes comparable to today’s dating back centuries and even millennia.

The evidence consists largely of reconstructions based on proxies such as tree rings, sediment cores and leaf fossils, although some evidence is anecdotal. Reconstruction of historical hurricane patterns, for example, confirms what I noted in an earlier post, that past hurricanes were even more frequent and stronger than those today.

The figure below shows a proxy measurement for hurricane strength of landfalling tropical cyclones – the name for hurricanes down under – that struck the Chillagoe limestone region in northeastern Queensland, Australia between 1228 and 2003. The proxy was the ratio of 18O to 16O isotopic levels in carbonate cave stalagmites, a ratio which is highly depleted in tropical cyclone rain.

What is plotted here is the 18O/16O depletion curve, in parts per thousand (‰); the thick horizontal line at -2.50 ‰ denotes Category 3 or above events, which have a top wind speed of 178 km per hour (111 mph) or greater. It’s clear that far more (seven) major tropical cyclones impacted the Chillagoe region in the period from 1600 to 1800 than in any period since, at least until 2003. Indeed, the strongest cyclone in the whole record occurred during the 1600 to 1800 period, and only one major cyclone was recorded from 1800 to 2003.

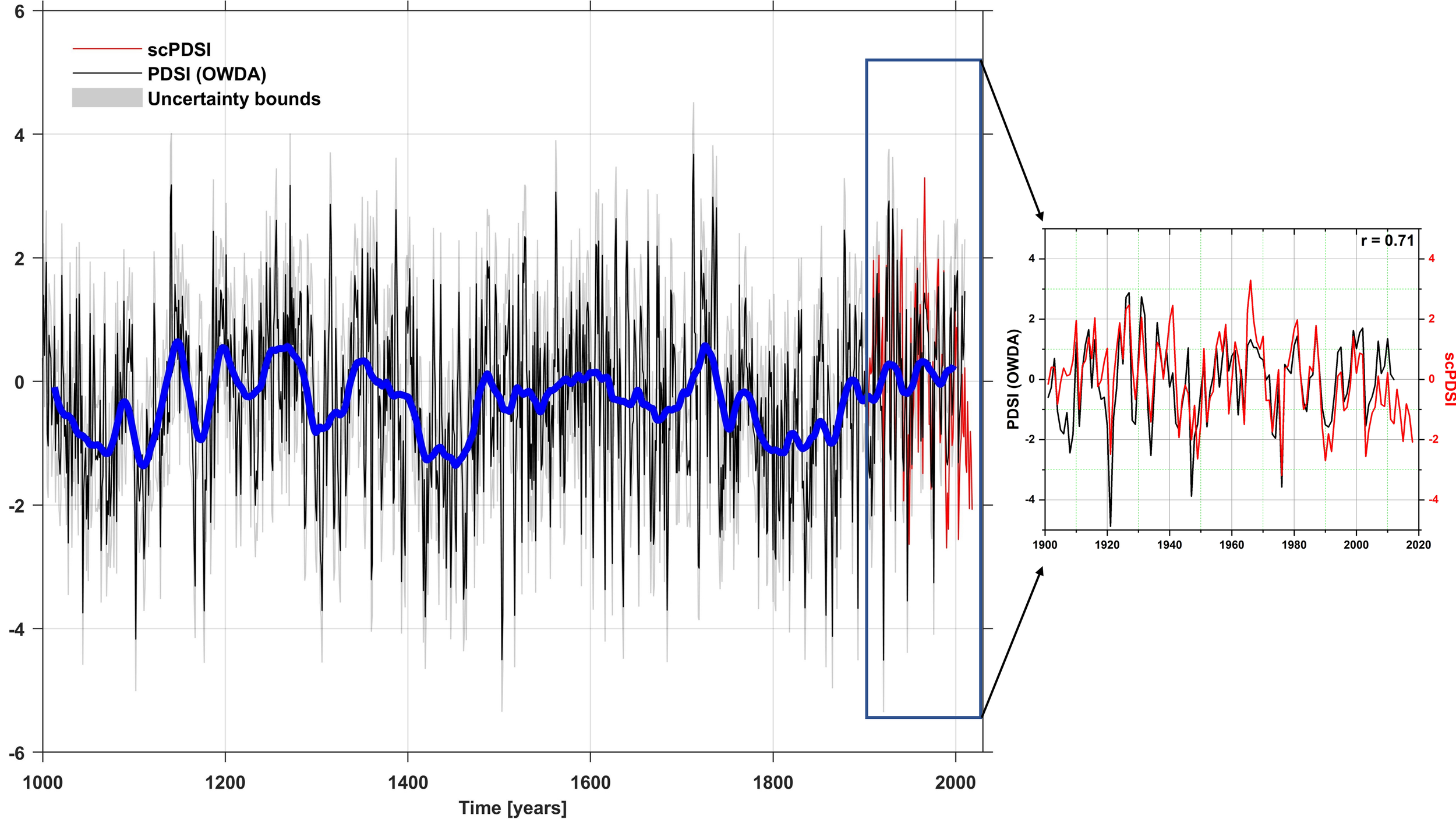

Another reconstruction of past data is that of unprecedently long and devastating “megadroughts,” which have occurred in western North America and in Europe for thousands of years. The next figure depicts a reconstruction from tree ring proxies of the drought pattern in central Europe from 1000 to 2012, with observational data from 1901 to 2018 superimposed. Dryness is denoted by negative values, wetness by positive values.

The authors of the reconstruction point out that the droughts from 1400 to 1480 and from 1770 to 1840 were much longer and more severe than those of the 21st century. A reconstruction of megadroughts in California back to 800 was featured in a previous post.

An ancient example of a megadrought is the 7-year drought in Egypt approximately 4,700 years ago that resulted in widespread famine, known as Famine Stela. The water level in the Nile River dropped so low that the river failed to flood adjacent farmlands as it normally does each year, resulting in drastically reduced crop yields. The event is recorded in a hieroglyphic inscription on a granite block located on an island in the Nile.

At the other end of the wetness scale, a Christmas Eve flood in the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany in 1717 drowned over 13,000 people – many more than died in the much hyped Pakistan floods of 2022.

Although most tornadoes occur in the U.S., they have been documented in the UK and other countries for centuries. In 1577, North Yorkshire in England experienced a tornado of intensity T6 on the TORRO scale, which corresponds approximately to EF4 on the Fujita scale, with wind speeds of 259-299 km per hour (161-186 mph). The tornado destroyed cottages, trees, barns, hayricks and most of a church. EF4 tornadoes are relatively rare in the U.S.: of 1,000 recorded tornadoes from 1950 to 1953, just 46 were EF4.

Violent thunderstorms that spawn tornadoes have also been reported throughout history. An associated hailstorm which struck the Dutch town of Dordrecht in 1552 was so violent that residents “thought the Day of Judgement was coming” when hailstones weighing up to a few pounds fell on the town. A medieval depiction of the event is shown in the following figure.

Such historical storms make a mockery of the 2023 claim by a climate reporter that “Recent violent storms in Italy appear to be unprecedented for intensity, geographical extensions and damages to the community.” The thunderstorms in question produced hailstones the size of tennis balls, merely comparable to those that fell on Dordrecht centuries earlier. And the storms hardly compare with a hailstorm in India in 1888, which actually killed 246 people.

Next: Challenges to the CO2 Global Warming Hypothesis: (10) Global Warming Comes from Water Vapor, Not CO2