Past Global Warming More Rapid than Today’s: The Younger Dryas

/Skeptics of the climate change narrative often point to periods of warming in the distant past when global temperatures were far above today’s, but CO2 levels were lower, as ruling out human emissions of CO2 as the cause of modern global warming. But this assertion is rejected by advocates of the CO2 narrative, who argue that current warming is happening far more rapidly than in any past episodes.

However, there are numerous examples of rapid climate change in the historical record, some as recently as the last ice age. One of the best documented is a period of climate upheaval known as the Younger Dryas, which occurred approximately 12,900 to 11,700 years ago and temporarily reversed the earth’s recovery from frigid glacial conditions.

The effect on temperature and ice accumulation in Greenland is illustrated in the figure below, but a similar phenomenon took place all over the Northern Hemisphere. The Younger Dryas is named after a wildflower, Dryas Octopetala, that thrives in very cold European climates.

As the earth slowly warmed from the ice age, the temperature (red line) suddenly took a steep upward turn – to almost present-day levels – around 15,000 years ago. This event is known as the Oldest Dryas and is clearly visible on the left of the figure. This was soon followed by the Younger Dryas, when the temperature plunged back to near-glacial conditions and which must have been devastating for early humans.

But then the Younger Dryas ended abruptly, with temperatures soaring upward again to where they would have been had the Dryas events not happened. By many accounts (see, for example, here and here), the mean annual global temperature rose by as much as 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit) in only 10 years.

That’s an increase of 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) in just one year – far in excess of modern global warming, in which the same 1-degree Celsius increase has taken more than 50 years.

However, the Younger Dryas is not an isolated instance of abrupt climate change in our planet’s past. As I discussed in a 2024 blog post, temperatures in Greenland rose suddenly and fell again at least 25 times during the last ice age, which spanned the period from about 115,000 to 10,000 years ago. Corresponding temperature swings occurred in Antarctica too, although they were less pronounced than those in Greenland.

The striking but fleeting bursts of heat are known as Dansgaard–Oeschger (D-O) events, named after palaeoclimatologists Willi Dansgaard and Hans Oeschger who examined ice cores obtained by deep drilling the Greenland ice sheet. They found a series of rapid climate fluctuations, when the earth warmed to near-interglacial conditions over just a few decades, and then gradually cooled back down to frigid ice-age temperatures.

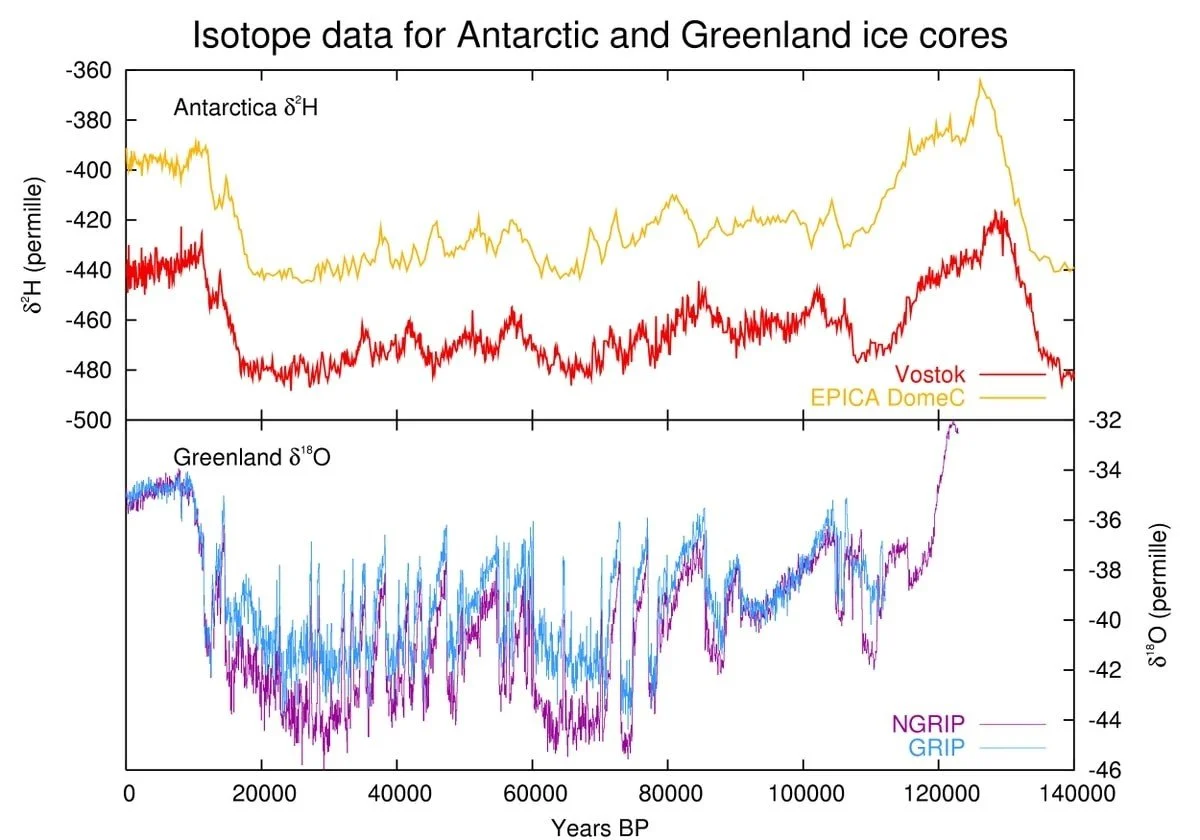

The phenomenon can be seen in the next figure, depicting ice-core data from both Greenland and Antarctica; two sets of measurements, recorded at different locations, are shown for each. The isotopic ratios of 18O to 16O, or δ18O, and 2H to 1H, or δ2H, in the cores are used as proxies for the past surface temperature in Greenland and Antarctica, respectively. The Younger Dryas is merely the last of 25 or 26 D–O events over the past 120,000 years, albeit an extra strong one.

Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the Younger Dryas. The leading hypothesis postulates that enormous amounts of freshwater were discharged into the North Atlantic Ocean about 12,900 years ago, in the form of rapidly melting icebergs disgorged from the massive Laurentide ice sheet which covered most of Canada and the northern U.S.

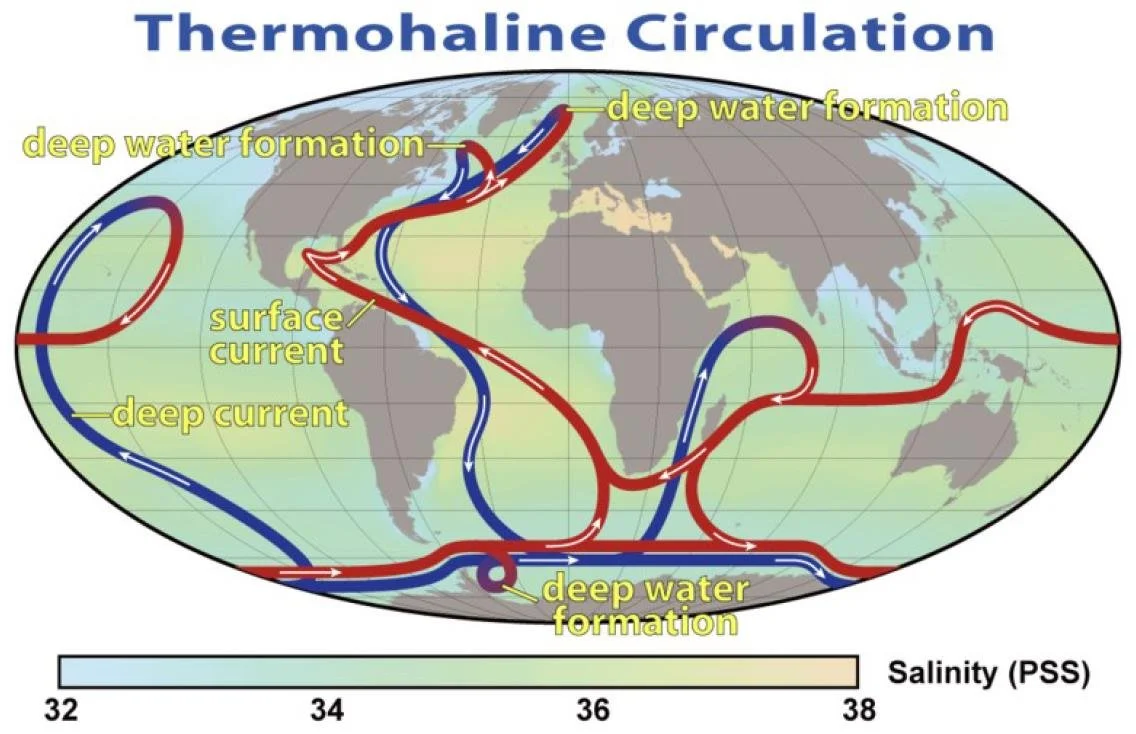

This vast influx of freshwater would have disrupted the deep-ocean thermohaline circulation (shown in the figure below) by lowering ocean salinity, which in turn suppressed deepwater formation and weakened the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation). Eventually, as the meltwater flux abated, the AMOC would have strengthened again, enabling the climate to recover.

A problem with this hypothesis is the timing: a second meltwater pulse, while slightly smaller than the first one 1,200 years earlier, occurred at the end of the Younger Dryas. Yet the second pulse didn't result in a similar weakening of the AMOC.

An alternative explanation is the impact hypothesis. This involves the impact of a large extraterrestrial object that burst in the atmosphere, creating fragments which struck various areas around the world 12,900 years ago. The fragments are thought to have sparked widespread wildfires and even caused a number of extinctions.

Proponents of the hypothesis point to geological layers known as “black mats,” as well as the formation of nanodiamonds, as evidence of past fiery events. But others dismiss such claims, saying that it’s equally likely that volcanic eruptions were the cause.

Next: Climate Alarmism and Net Zero Strategy on the Wane