Has the Sun’s Role in Climate Change Been Trivialized?

/Central to the narrative that climate change comes largely from human emissions of greenhouse gases is the assertion that the sun plays almost no role at all. According to its Fifth Assessment Report, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) attributes no more than a few percent of total global warming to the sun’s influence.

But the exact amount of the solar contribution to global warming is critically dependent on how much the sun’s heat and light output, known technically as the TSI (total solar irradiance), has varied since the 19th century. According to an international team of scientists in a recently published paper, different estimates of the TSI lead to different conclusions about global warming – ranging from the sun making a trivial contribution, which backs up the IPCC claim that recent warming is mostly human-caused, to the opposite conclusion that global warming is mostly natural and due to changes in solar activity.

How can there be such a wide discrepancy between these two positions? Over the approximately 11-year solar cycle, the TSI varies by only a tenth of one percent. However, long-term fluctuations in the sun’s internal magnetic field cause the baseline TSI to vary over decades and centuries.

This can be seen in the somewhat congested figure below, which depicts several reconstructions of the TSI since 1850 and shows variations in both the TSI baseline and its peak-to-peak amplitude. The curve plotted in black forms the basis for the current CMIP6 generation of computer climate models; the curve in yellow was the basis for the previous CMIP5 models featured in the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report.

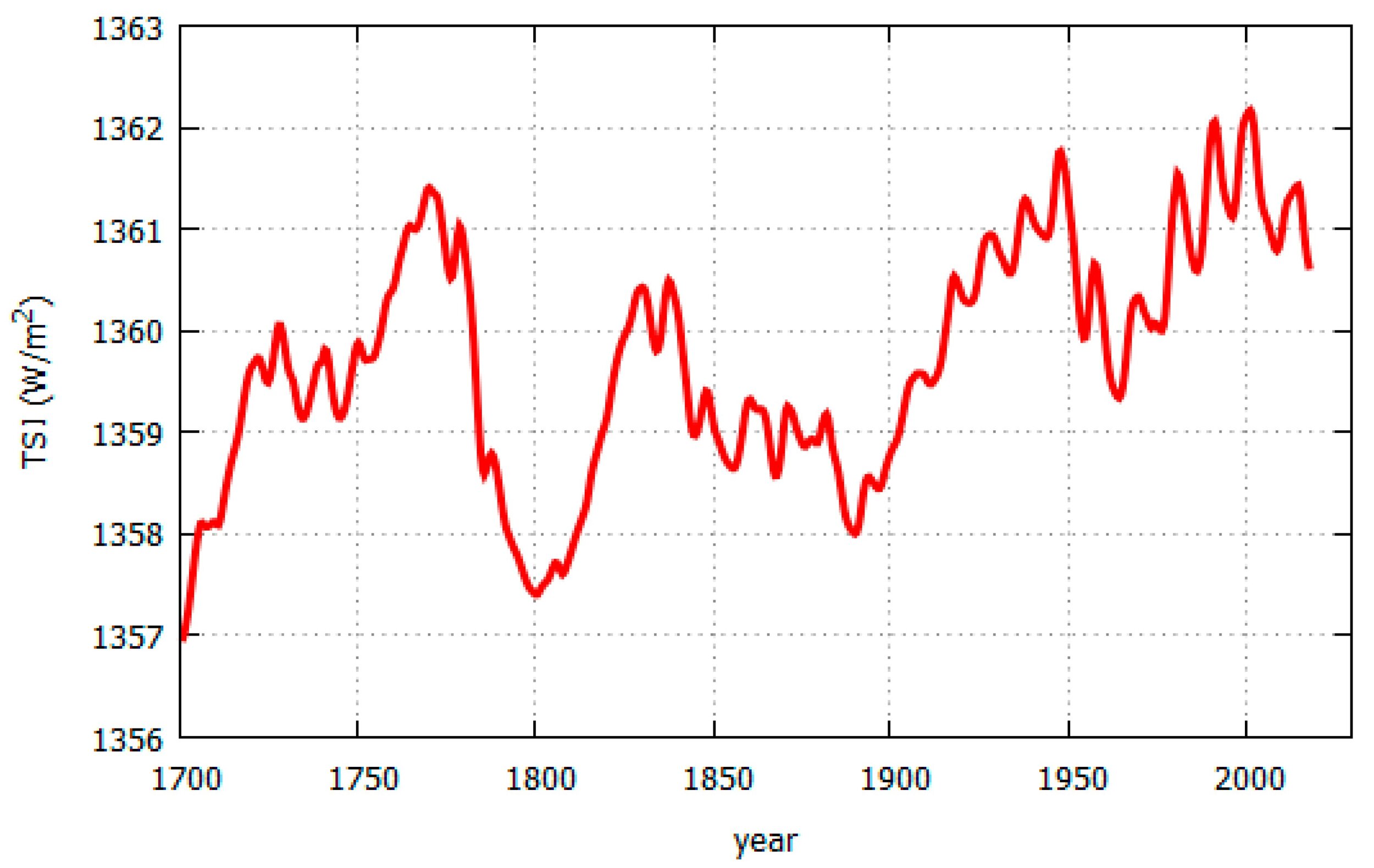

A rather different reconstruction of the TSI since 1700 is shown in the next figure, based on an earlier solar irradiance model augmented with recent satellite data. You can see that in this reconstruction, the TSI since 1850 exhibits much larger fluctuations – from 1358 to 1362 watts per square meter – compared with the reconstruction above, in which the variation since 1850 is only from about 1360.5 to 1362 watts per square meter.

The dramatic difference between the two estimates of the TSI arises from rival sets of satellite data. Satellite measurements of TSI began in 1978, the two main sources of data being the Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium’s so-called ACRIM (Active Cavity Radiometer Irradiance Monitor) composite, and the World Radiation Center’s PMOD (Physikalisch-Meteorologisches Observatorium Davos) composite.

The ACRIM composite implies that the TSI rose during the 1980s and 1990s but has fallen slightly since then, as seen in the second figure above. The PMOD composite implies that the TSI has been steadily dropping since the late 1970s, a trend just visible in the first figure. The PMOD composite, showing a decline in solar activity during the period after 1975 in which global temperatures went up, therefore downplays the sun’s role in global warming. On the other hand, the ACRIM composite indicates an increase in solar activity over the same period, so supports the notion that global temperatures are strongly linked to the TSI.

The ACRIM satellite data set and the PMOD data differ in the procedures used to bridge a two-year gap in ACRIM data around 1990. The gap in data gathering occurred after the launch of a new ACRIM satellite was delayed by the Challenger disaster. It’s these disparate gap-bridging procedures that result in the ACRIM and PMOD composite data showing such different behavior of the TSI during the most recent solar cycles 21 to 23.

The authors of the recent paper also discuss other TSI reconstructions, some of which support the ACRIM data and some of which back the rival PMOD data. Rather than passing judgment on which dataset is the better representation of reality, the authors urge the climate science community to consider all relevant estimates of the TSI and not just the one illustrated in the first figure above. But they conclude that, contrary to the current narrative, the question of how much the sun has influenced recent global temperatures – at least in the Northern Hemisphere – has not yet been answered satisfactorily.

The researchers go on to comment: “The PMOD dataset is more politically advantageous to justify the ongoing considerable political and social efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the assumption that the observed global warming since the late 19th century is mostly due to greenhouse gases.” They add that political considerations have been acknowledged as one of the motivations for the development of the PMOD composite as a rival dataset to the ACRIM measurements.

Next: Latest UN Climate Report Is More Hype than Science