No Evidence That Climate Change Causes Weather Extremes: (6) Heat Waves

/This Northern Hemisphere summer has seen searing, supposedly record high temperatures in France and elsewhere in Europe. According to the mainstream media and climate alarmists, the heat waves are unprecedented and a harbinger of harsh, scorching hot times to come.

But this is absolute nonsense. In this sixth and final post in the present series, I’ll examine the delusional beliefs that the earth is burning up and may shortly be uninhabitable, and that this is all a result of human-caused climate change. Heat waves are no more linked to climate change than any of the other weather extremes we’ve looked at.

The brouhaha over two almost back-to-back heat waves in western Europe is a case in point. In the second, which occurred toward the end of July, the WMO (World Meteorological Organization) claimed that the mercury in Paris reached a new record high of 42.6 degrees Celsius (108.7 degrees Fahrenheit) on July 25, besting the previous record of 40.4 degrees Celsius (104.7 degrees Fahrenheit) set back in July, 1947. And a month earlier during the first heat wave, temperatures in southern France hit a purported record 46.0 degrees Celsius (114.8 degrees Fahrenheit) on June 28.

How convenient to ignore the past! Reported in Australian and New Zealand newspapers from August, 1930 is an account of an earlier French heatwave, in which the temperature soared to a staggering 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit) in the Loire valley, located in central France. That’s a full 4.0 degrees Celsius (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) above the so-called record just mentioned in southern France, where the temperature in 1930 may well have equaled or exceeded the Loire valley’s towering record.

And the same newspaper articles reported a temperature in Paris that day of 38 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit), stating that back in 1870 the thermometer had reached an even higher, unspecified level there – quite possibly above the July 2019 “record” of 42.6 degrees Celsius (108.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

The same duplicity can be seen in proclamations about past U.S. temperatures. Although it’s frequently claimed that heat waves are increasing in both intensity and frequency, there’s simply no scientific evidence for such a bold assertion. The following figure charts official data from NOAA (the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) showing the yearly number of days, averaged over all U.S. temperature stations, from 1895 to 2018 with extreme temperatures above 38 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit) and 41 degrees Celsius (105 degrees Fahrenheit).

The next figure shows NOAA’s data for the year in which the record high temperature in each U.S. state occurred. Of the 50 state records, a total of 32 were set in the 1930s or earlier, but only seven since 1990.

It’s obvious from these two figures that there were more U.S. heat waves in the 1930s, and they were hotter, than in the present era of climate hysteria. Indeed, the annual number of days on which U.S. temperatures reached 100 degrees, 95 degrees or 90 degrees Fahrenheit has been steadily falling since the 1930s. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency)’s Heat Wave Index for the 48 contiguous states also shows clearly that the 1930s were the hottest decade.

Globally, it’s exactly the same story, as depicted in the figure below.

Of the seven continents, six recorded their all-time record high temperatures before 1982, three records dating from the 1930s or before; only Asia has set a record more recently (the WMO hasn’t acknowledged the 122 degrees Fahrenheit 1930 record in the Loire region). And yet the worldwide baking of the 1930s didn’t set the stage for more and worse heat waves in the years ahead, even as CO2 kept pouring into the atmosphere – the scenario we’re told, erroneously, that we face today. In fact, the sweltering 1930s were followed by global cooling from 1940 to 1970.

Contrary to the climate change narrative, the recent European heat waves came about not because of global warming, but rather a weather phenomenon known as jet stream blocking. Blocking results from an entirely different mechanism than the buildup of atmospheric CO2, namely a weakening of the sun’s output that may portend a period of global cooling ahead. A less active sun generates less UV radiation, which in turn perturbs winds in the upper atmosphere, locking the jet stream in a holding or blocking pattern. In this case, blocking kept a surge of hot Sahara air in place over Europe for extended periods.

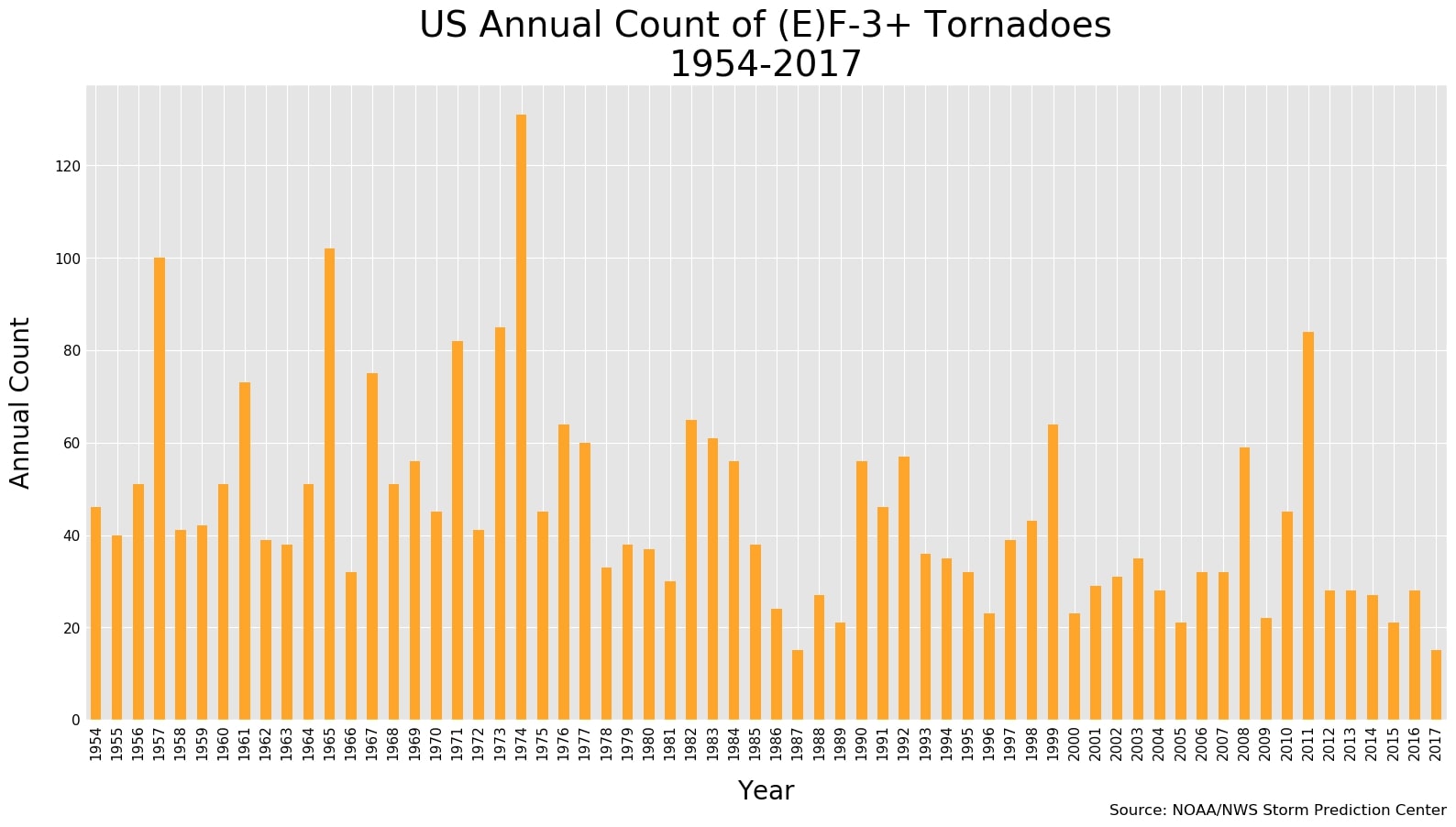

It should be clear from all the evidence presented above that mass hysteria over heat waves and climate change is completely unwarranted. Current heat waves have as little to do with global warming as floods, droughts, hurricanes, tornadoes and wildfires.

Next: No Evidence That Heat Kills More People than Cold